Juliet.

I want to tell you about this woman; my aunt Juliet, Julie, or “Bibi” as she was known in our family. I want to tell you what I tried to tell everyone at her memorial, whilst choking back tears, my whole body trying to contain all I was feeling to no avail.

In the days leading up to the memorial I had been thinking of what I might like to say, or a specific story I might like to share. When I started looking back, what came up was every memory I ever had with her, all at once. I thought of when I first started getting to know her, when her, my cousin Julien and my uncle Jim moved to Brisbane from The Philippines so that she could complete her Masters in Applied Linguistics. Growing up away from my extended family, Tita Julie was the first aunt I was able to form a real relationship with. At that time in my life, I was a depressed, angry teenager. I didn’t know her, yet I instinctively softened around her. I knew it would be safe for me to open my heart, even at a time I kept my heart closed to most.

It wasn’t hard to confide in her, but that’s because she made it so easy. She held space; you felt seen, you felt heard. In this way we were all able to have an equally unique and meaningful relationship with her, because her authenticity allowed us to be who we are so freely around her, like coming home. She knew how to ask questions without making you feel judged; she approached the world and people with arms wide open, flaws and all—only people who meet their own shortcomings with love can meet yours with the same.

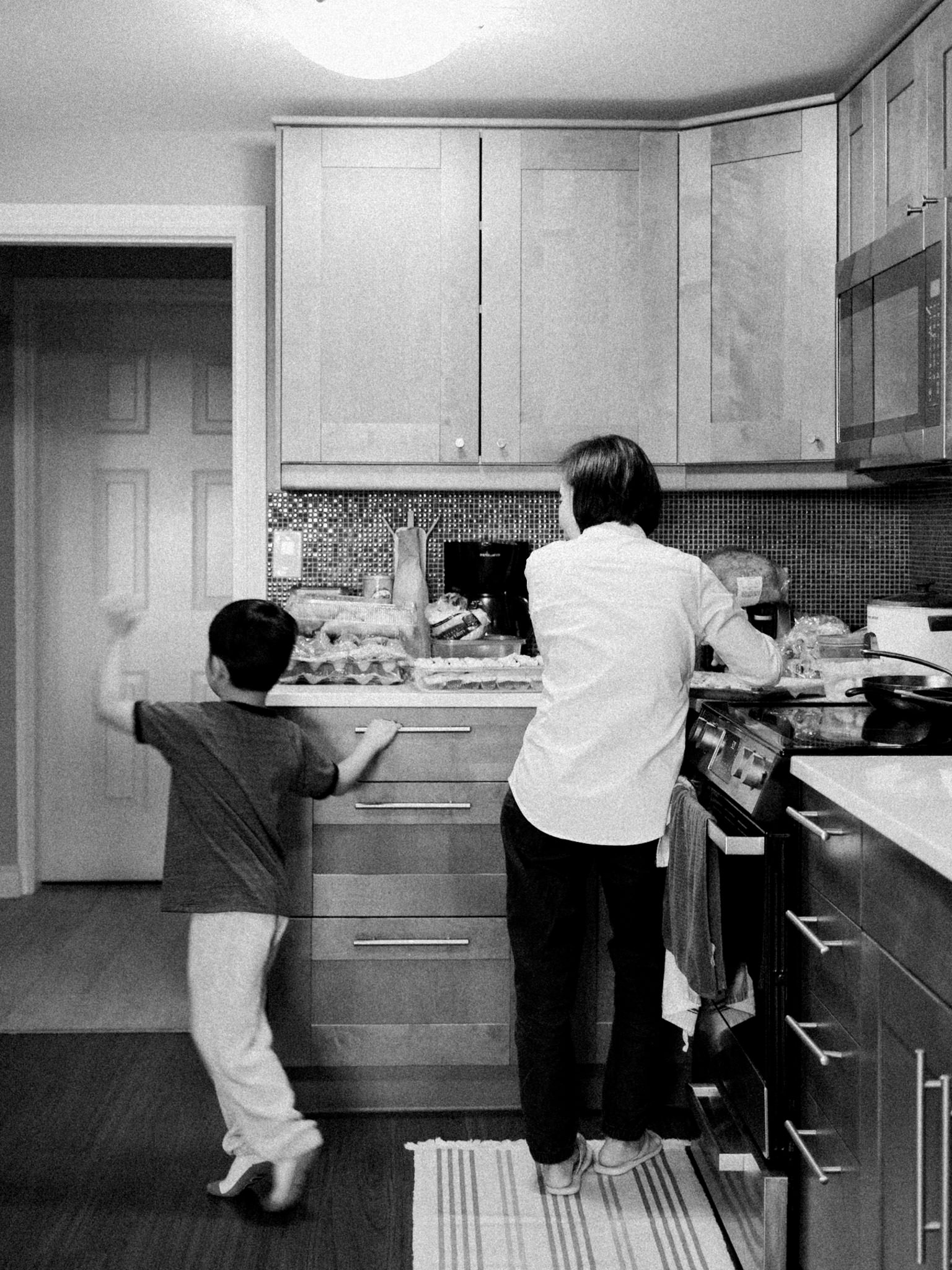

She was strong and sure of herself; strong like how a mountain or an old tree can stand and quietly weather it all. She showed us what grace, strength and faith in the face of overwhelming adversity looked like. We watched her deteriorate in front of us and sometimes I think it tore us apart more than it did her. She hiked Wedgemount Lake, one of the most difficult hikes in Garibaldi Provincial Park, with Stage 4 terminal cancer only 3 years ago. She journeyed home to The Philippines last year to surprise my grandmother on her 88th birthday, putting her energy towards organising every final detail for that family reunion (the one she most likely knew would be her very last). There’s a video of her from that time, dancing for my grandmother with my mother and their other sisters; her body exhausted, in pain, and riddled with cancer; her spirit outshining it all anyway.

And oh, how she loved to laugh (I was always in hysterics around her, my cousin and my uncle). In the end, even in her bed at the hospice, she was cracking jokes; one night, she told the nurse who was washing her up that she was “bored” and that she would like to do zumba—so my cousin and I danced for her, in that little room just 4 days before she died.

Every moment, however ordinary, has been marked by the significance of who she was; of how she showed up for me, for her life, and for all of us. She was ever-present and in the moment with you; she was so full of life, and she never failed in her ability to perceive, to be intuitive, to be kind and empathetic. That will be how she lives on in all of us; that will be how I honour her throughout my life moving forward.

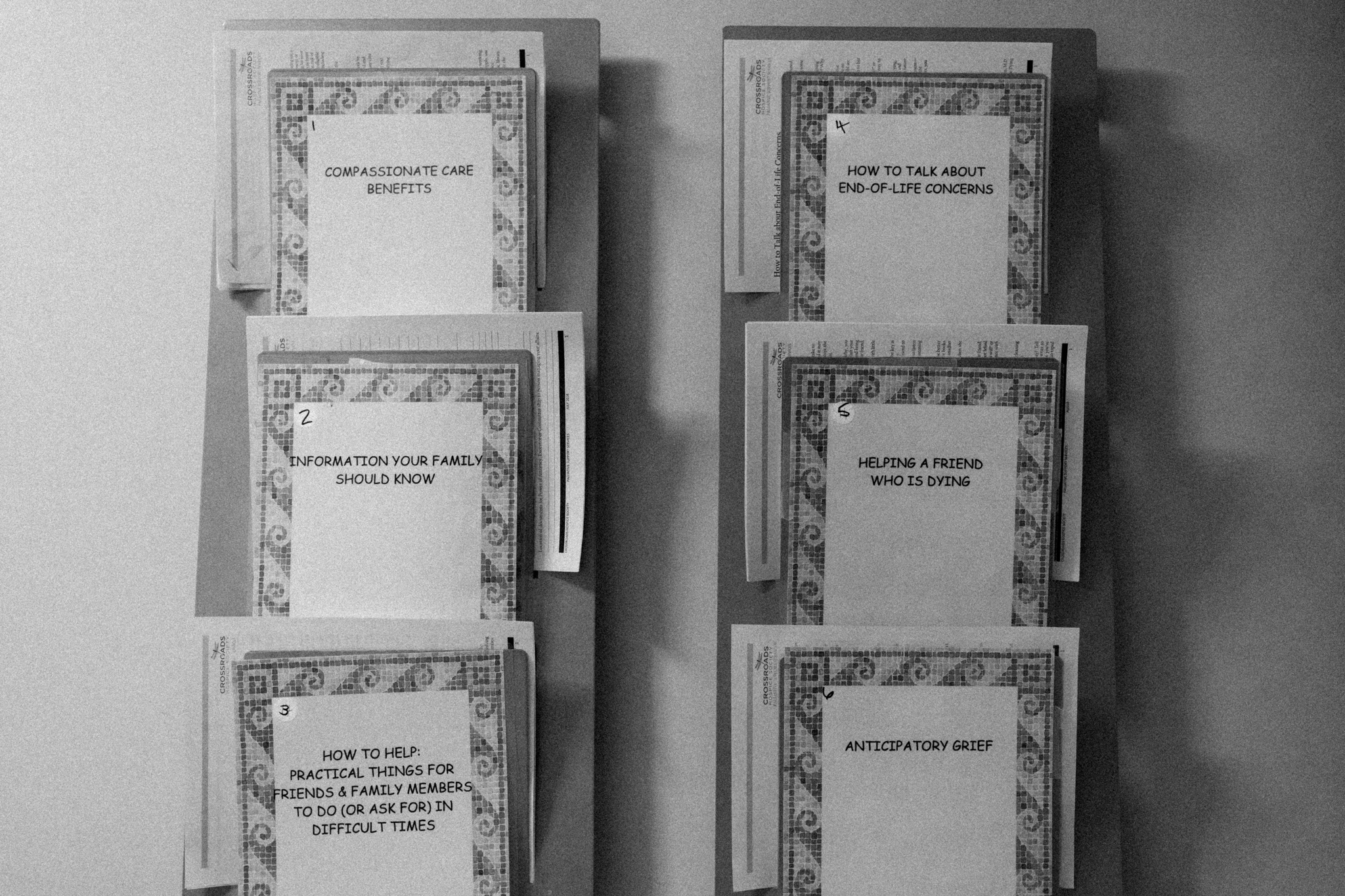

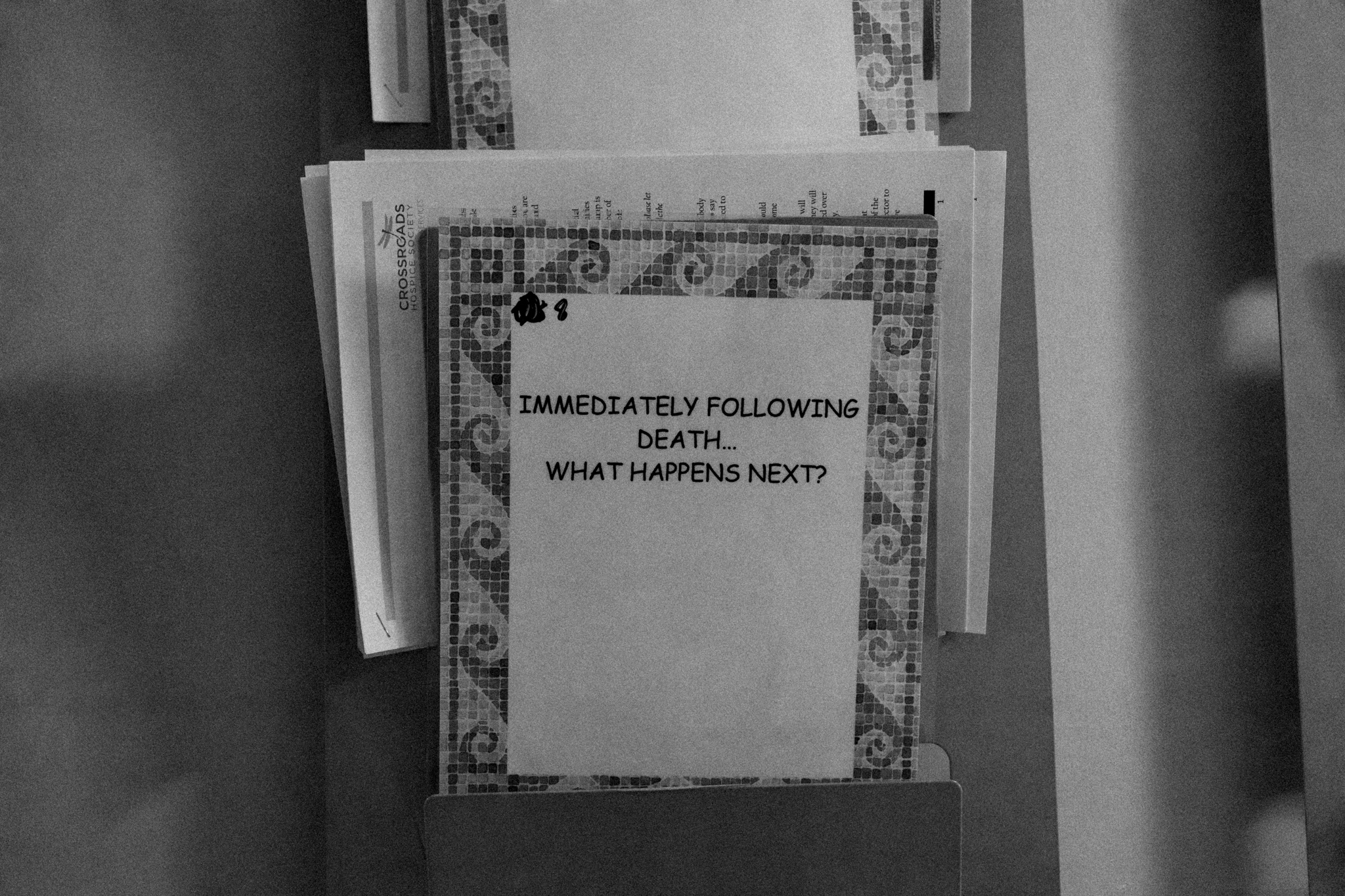

All year, my grief for her was an undercurrent; not yet allowing myself to be destroyed by something yet to happen. A way of preserving the precious time I had with her; a way of ensuring I would be able to be fully present in every moment I had with her, enjoying our time together. We would all talk about what was to happen openly and honestly, and in that way she prepared us all for the moment that was to come.

Her death was like a catalyst. When I cried for her, it was as if I opened the gate to all the other hurt I had been keeping out of reach, allowing myself to grieve everything else my heart had broken over in the last year. Finally, finally I cracked, and could let the healing begin.

Grief surprises me in unexpected moments; really, there is an ever-present melancholy, but grief itself is sharp, coming at me from the sides and from the shadows. A week after her death I drove past a Greyhound bus on the way to work; a fairly ordinary moment if not for the fact it brought forward a stark recollection of how she used to catch the bus from Vancouver all the way back to Calgary for her check-ups in the year before she died. The tears came as suddenly as the memory did. Checking the calendar and remembering that in October last year, it was with her that my siblings were waiting to surprise me at Vancouver airport when they visited me from Australia. Or remembering, out of the blue, how I lit a candle for her 3 years ago, in the Basilique de Notré-Dame in Montréal when she was still alive—terminal, yes, but very much alive; a moment I had all but forgotten until I saw an old church during a scene in a TV show I was watching. I don’t think I ever told her about that.

My brain digs, searching in its tiniest crevices for moments with her, as if bringing forth those moments will keep her alive. They do, and they don’t. As if playing those memories over and over, trying to grasp every detail and keep it as vivid as it was the last time, will mean that all of a sudden I will be able to call her like I used to. If I concentrate hard enough to hear her calm and compassionate voice, will she actually be speaking? If I close my eyes, I can even see her eyes and the way she would smile. I am scared that one day I will forget—was it this way that she smiled, or was it another?

This, for me, is the power of photography, and what it means to me. To be able to capture the truth of our lives and the truth of who we are, so that we have something tangible of the ones we love to look back on when they are gone, and something to leave behind for when we ourselves have departed.

And then, it was her memorial weekend. Her passing was, in a way, sudden. It was as if she had simply been waiting for my other aunt to arrive, the last of her visitors, before leaving us. I had just flown out of Vancouver about 12 hours before she died. I had only just given her a kiss on the forehead the night before, telling her I loved her and that I would see her soon (although I think we both knew what I meant by that). I felt robbed, not having been there for her final moments, but knowing she passed in the arms of my uncle, cousin, my cousin’s partner, my mother and my aunt was comfort enough. She was ready to go, and she had suffered enough.

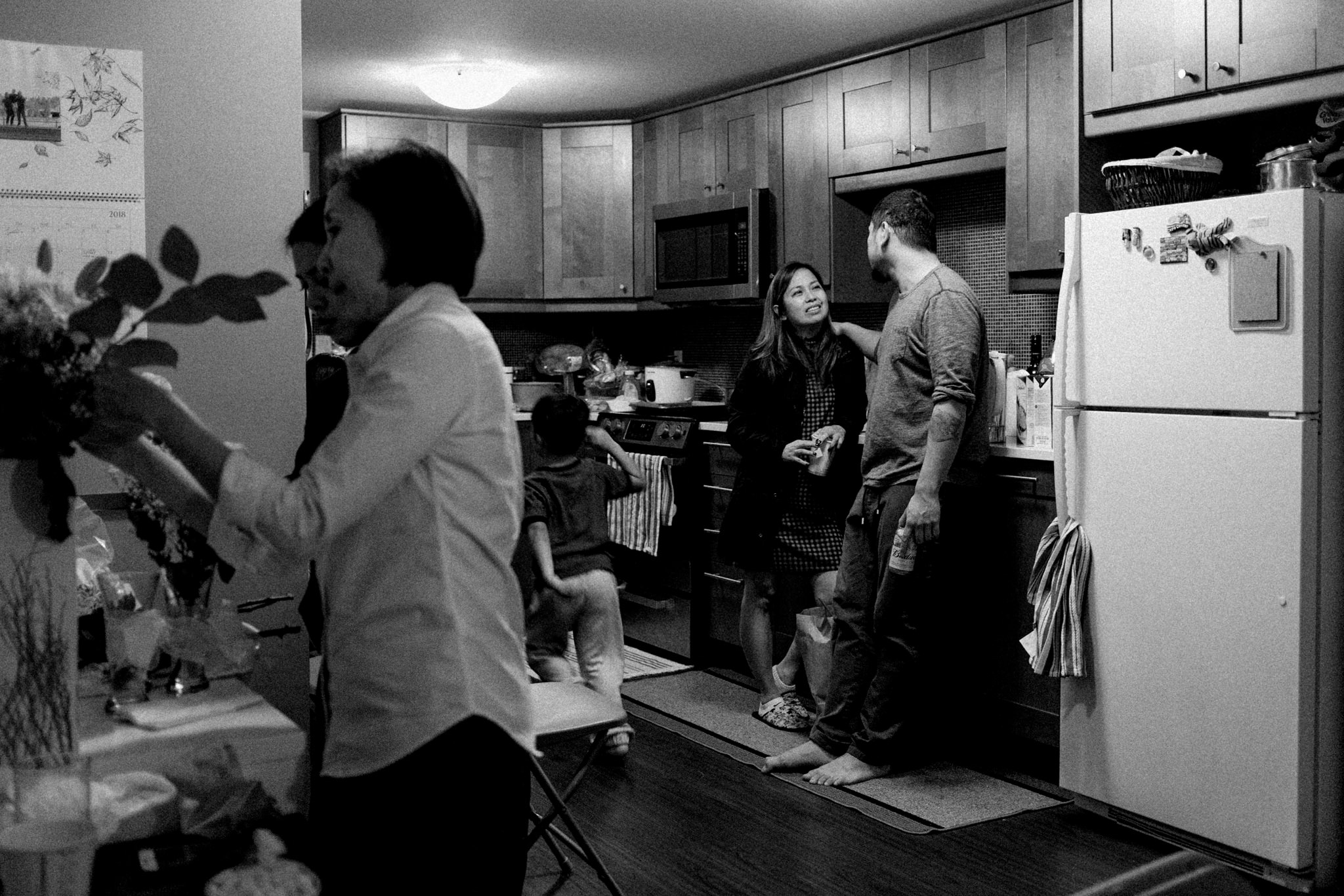

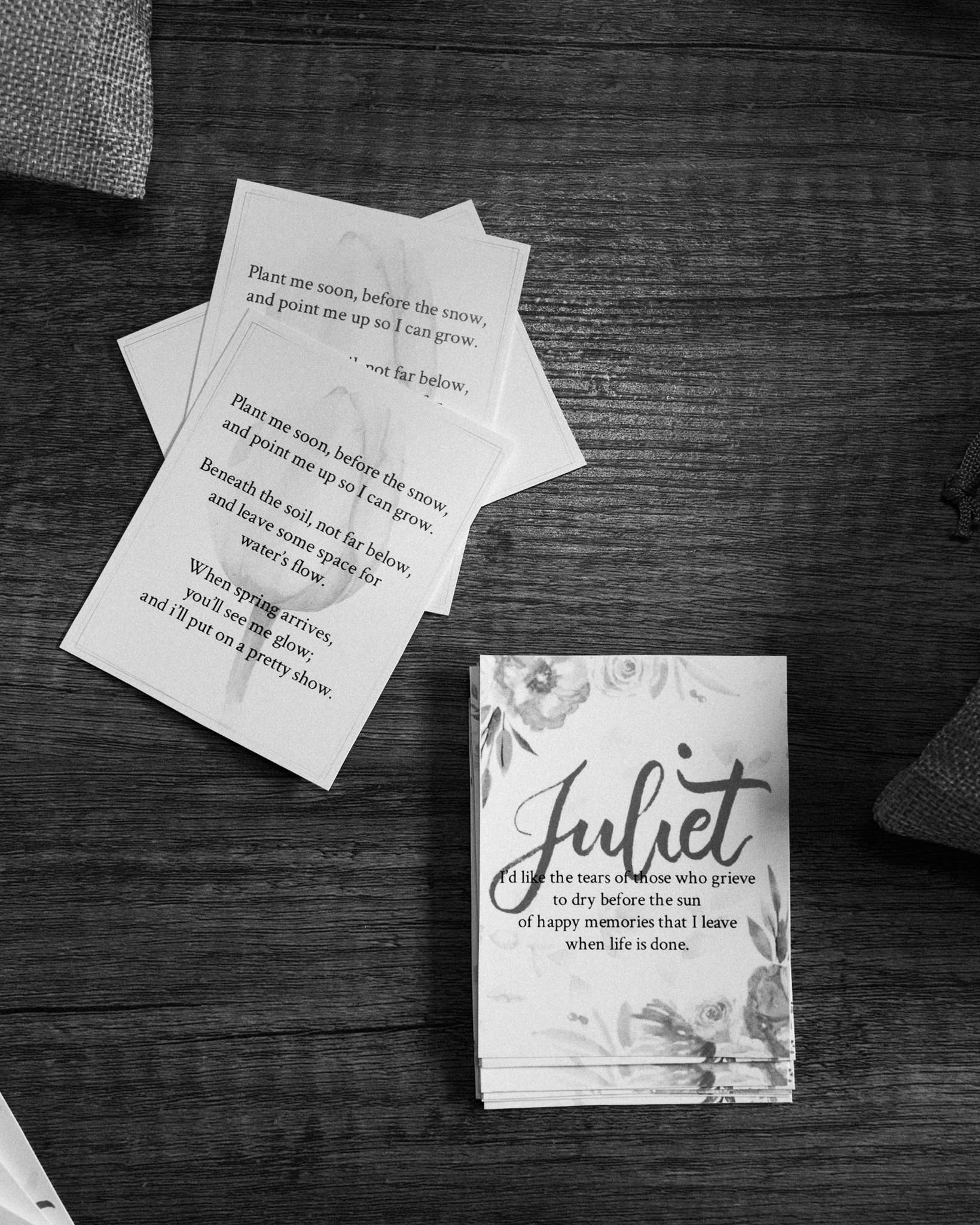

She had been planning her own memorial for months together with my cousin and some of our other aunts. So in the fortnight after her passing, they came together and carried out her final wishes—organising for the service to be outdoors, at her favourite park; making bouquets of yellow and white flowers; putting tulip bulbs (her favourite flower) into little bags to give to guests, each with a different photo of her attached, as we all remembered her differently. I like to think the photo I picked, in the end, is the one she would have wanted me to have.

Even in her death she was weaving wonders, bringing family together from The Philippines, Australia, United States and elsewhere in Canada to celebrate her life. We talked deeply, we cried fully, we laughed wholly, we danced wildly and we sung loudly, just as she would have wanted; sometimes it felt as if she was there, alive in all of us, yet the room felt emptier without her. I am finding it hard to describe this feeling—simultaneously longing for someone to be there who will never show up, but feeling the weight of their presence in the room, like a warm glow all around.

We wished you were here to dance with us, Tita—but you’re in a far better place than the rest of us, now.